Cold War paranoia aside, the future from the perspective of the late fifties was to be an optimistic place. A world of sleek, swooping contours and starlite neon, fishbowl helmets and jetpacks, lunar rovers, moving sidewalks, rocket-powered roller skates, and squelchy theremin-based pop tunes. Unfortunately, economics and politics have since forced us down a grimmer path to where our future likely has more in common with the charred bleakscapes of Blade Runner or Mad Max.

The TWA Flight Center, which opened in 1962 at the airport now called JFK, was the brainchild of Eero Saarinen, a Finnish-American architect who had designed not only the St Louis Gateway Arch, but also the iconic "tulip chair" as seen on the bridge of Star Trek's USS Enterprise. The Saarinen "Head House," as the main structure was called, was a prime example of what is considered Googie or Populuxe architecture, with its thin shell concrete roof, ceramic tiles, and curvilinear mezzanine. The sculptural contours were intended to suggest a soaring bird (though to me it looks more like a Cylon Raider). Predictably, it stirred up the ire of conservative critics of the era, while at the same time winning awards for its bold design. The terminal stayed in operation for four decades until TWA eventually hit the skids at century's end. Since then it has been shuttered to the public, largely, but not entirely, forgotten.

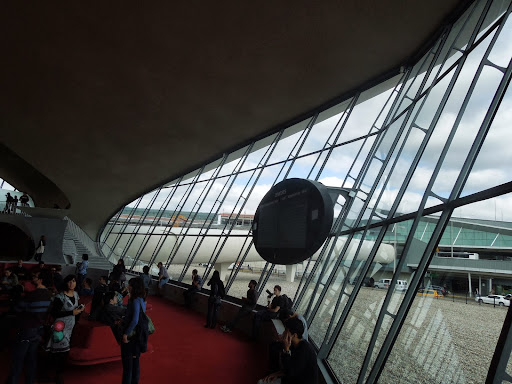

For a few hours on an autumnal Sunday, the good people of Open House New York arranged for the guard dogs to be chained up and the fence de-electrified. Charging down the red carpeted tube which connects the Flight Center to the functional area of the airport, I discovered an open realm of space age contours straight out of The Jetsons. I wasn't alone. The retrofuturist lobby swarmed with history buffs and photohounds, amateur and otherwise, eager to capture this rare sighting.

Technology has progressed at a dizzying pace since the Sixties. A list of devices and developments they couldn't possibly have conceived of then which we now take for granted could fill volumes. In small type with narrow margins. So why does it feel, when gazing around within a stunning time capsule such as this, that they knew something that we don't?

The Flight Center has been listed under the National Register of Historic Places, so fortunately it's not going anywhere soon (unlike the less fortunate UFO-shaped Pan Am Worldport, which lie in ruins as I AirTrained by). JetBlue, who now owns the building, is having it restored but isn't quite sure what to do with the space. Some suggestions bandied about include turning it into a conference center, aviation museum, or restaurant. I believe the current plan is to adapt it as part of a luxury hotel. Make it a tanning salon for all I care, just so long as they preserve this fleeting glimpse of The Tomorrow That Never Was.

Tales from the Big Onion

18 October 2013

TWA Flight Center

03 March 2013

The Voodoo Museum

Much credit for the sinister reputation Voodoo (shall we say) enjoys can be attributed to the 1932 Bela Lugosi film White Zombie, which recast the colorful religion as a Hollywood genre. As with most things, the truth is more nuanced. The origins of Voodoo trace back to the Fon people of West Africa, in what is now Republic of Benin. The name comes from the Fon word for spirits, "Vodoun." The 18th century slave trade brought this spiritual practice and folklore (reluctantly) to the New World where it mingled with Creole customs and Catholic rituals, ultimately resulting in something altogether unique.

An important element of the Voodoo practice is gris-gris, which refers to magic objects (dolls, candles, charms, amulets) as well as the incantation of them. The purpose of objects is primarily for attracting love, power, and fortune, and for undoing hexes. Despite their menacing image in our culture, Voodoo dolls are usually used to bless, rather than curse. Pins are stuck into the doll not to cause pain, Temple of Doom-style, but to attach a photo of the person who is to be blessed (or cursed). Gris-gris bags contain ingredients which represent spirits and bring good luck to the bearer.

Women's dominant role in Voodoo stems from gratitude to a female spirit named Aida Quido for helping the enslaved survive the horrific ocean voyages to the New World. Priestess are called queens, while priests are known as doctors. Voodoo queens typically preside over ceremonies and ritual dances. Voodoo is sometimes known as a "dancing religion" due to the fundamental role physical communion plays in the ceremonies. The dances and rituals of Voodoo were a strong influence on what would eventually evolve into American jazz.

The New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum was opened on Dumaine Street in 1972 by a local artist named Charles Massicot Gandolfo, or as he was popularly known, "Voodoo Charlie." The mission statement of the museum is to preserve the legacy of New Orleans’ Voodoo history and culture. The jam-packed museum consists of two shoebox-sized rooms and a hallway, plus a shop in front selling gris-gris bags, dolls, and potions. Near the entrance hangs a striking portrait of New Orleans' premier Voodoo Queen, Marie Laveau, the legendary oracle who specialized in love potions and healings. Beyond this are shelves of skulls bathed in a crimson glow, cabinets full of curios, and altars littered with coins, photos, beads, and lipsticks left by visitors as tributes. The centerpiece of the far room is a wishing stump, where wishes written on slips of paper can be dropped into its hollow body. A sign posted beside the stump recommends wrapping your paper around an offering of money, which presumably will expedite your wish's coming true.

A three-headed ju-ju, which mocks evil spirits with its protruding tongue. This one was carved by voodooist Herbert "Coon" Singleton. Ju-ju is a type of gris-gris partly constructed from hair or bone, something which was once alive.

An assortment of voodoo dolls.

Rougarou, a Cajun hybrid of zombie, vampire, and werewolf who prowls the swamps outside of New Orleans, sucking blood and stealing souls.

26 February 2013

The Garden District

A stroll through New Orleans' Garden District.

A streetcar named Charles.

This mansion once belonged to Trent Reznor from Nine Inch Nails, now owned by actor John Goodman.

The Brevard House, built for a wealthy merchant in 1857. Novelist Anne Rice lived here from 1989 to 2004.

Peace frog.

This house is certified "OK."