There are a slew of historical landmarks in Manhattan, commemorating everything from presidents to punks. But one of my favorites has to be the plaque that signifies "Pear Tree Corner" on an unassuming little streetcorner on the Lower East Side.

In 1647, former New Amsterdam governor Peter Stuyvesant (sometimes known as "Pegleg Pete" after losing a leg in a sea battle with Spain over the island of Saint Martin) returned from a voyage to Holland with, of all things, a pear tree in his cargo. He affectionately planted this tree on his 62-acre estate, at what is now the northeast corner of East 13th Street and Third Avenue. The tree was fruitful for over two centuries as the landscape around it gradually transformed from farmland to city block, until one fateful day in 1857 when a horrendous horse-drawn carriage pile-up effectively sent it to that Great Garden in the sky.

By that time a small apothecary had opened on the corner, supplying medicinal herbs to the inhabitants of what was coming to be called the Lower East Side. Over the years the Brunswick Apotheke, as it was once called, evolved into Kiehl's Pharmacy.

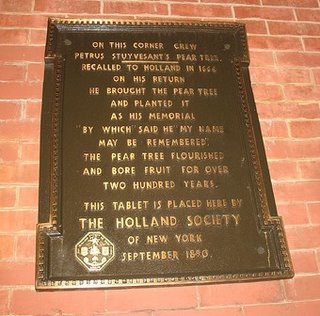

In 1890, in an effort to preserve the memory of Dutch presence in Manhattan, the Holland Society affixed a plaque to the wall of the pharmacy, marking the spot where the tree had stood. Unfortunately the building fell into disrepair over the years, and in 1958 Kiehl's Pharmacy relocated up the street to more modern digs. The original building was slated for demolition and the plaque wound up at St Mark's Church in-the-Bowery, where Stuyvesant had been interred, since no one else seemed to want it.

But the story doesn't end there. A half-century later, with a sudden rekindling of interest in its roots, Kiehl's returned to its original, newly renovated location at Pear Tree Corner and promptly demanded the now quite weatherbeaten plaque be restored. Following a brief proprietary tug-of-war, mark and marker have now been reunited. See for yourself.